Working with GANs is often imagined as fast, automated, and frictionless. In practice, it is slow, material, and full of constraint.

Before any image can be generated, time is spent curating the dataset; selecting images that hold both difference and coherence. Too much sameness and the model collapses into repetition; too much variation and it loses its sense of form. This process can take days: gathering, sorting, resizing, naming, and composing with what belongs together.

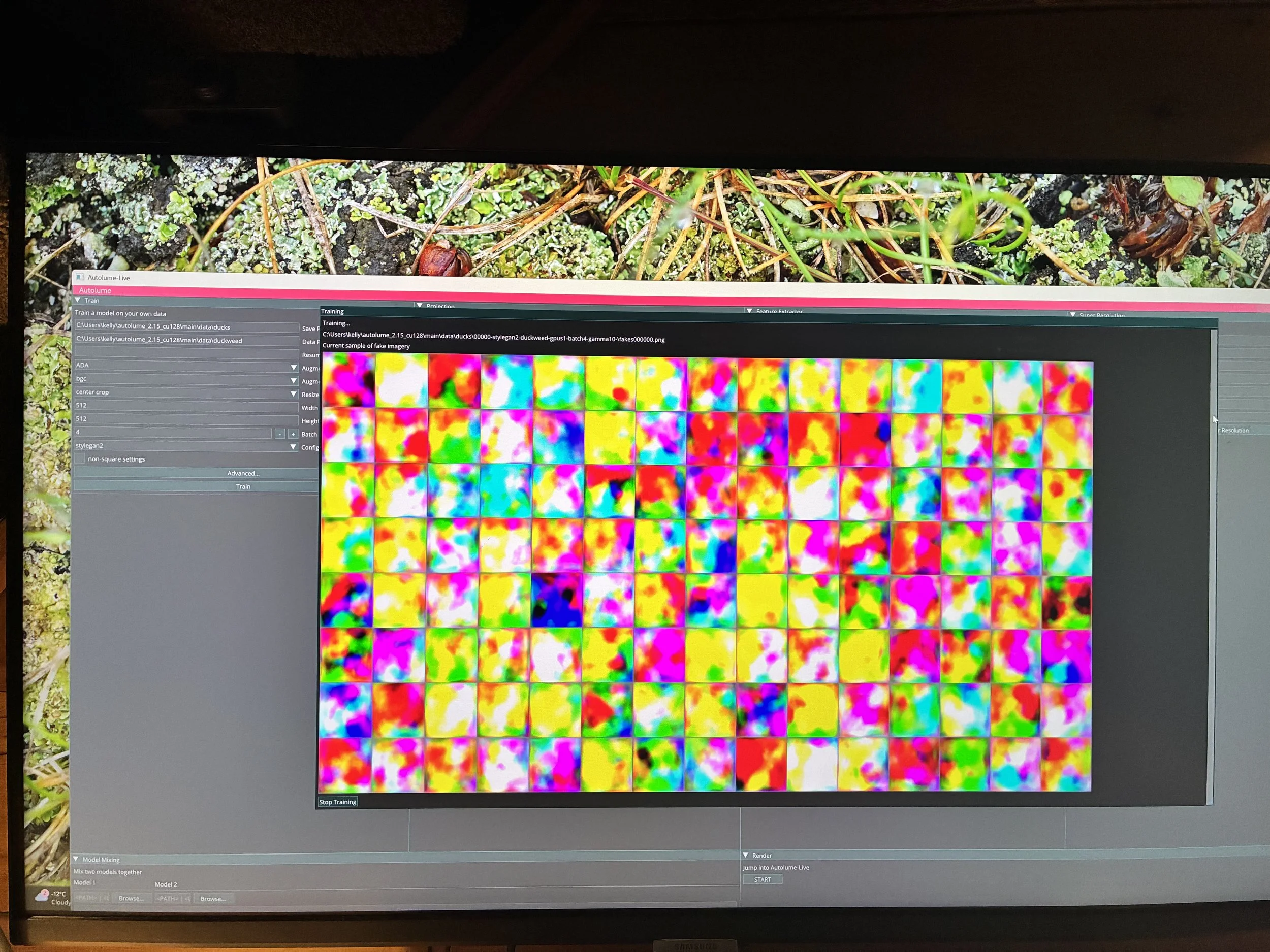

Then come the limits of the machine itself. Batch size, image resolution, and model architecture must be tuned to what my GPU can hold without crashing. These are not abstract parameters but negotiations with heat, memory, and capacity and reminders that this “learning” is grounded in very real, very finite hardware on my desk.

Training is slower still. Once started, it may run for hours or days, with no guarantee of success. Progress reveals itself gradually: a blur becomes a form, noise begins to hint at structure. There is no rushing this. The system learns in tiny increments, and I learn alongside it; when to stop, when to wait, when to let it keep becoming.

This slowness demands patience and care. It resists the fantasy of instant output and instead aligns more closely with practices of fermentation, composting, or ecological growth. Like SCOBYs, lichens, or pond ecologies, the model needs time to attune to its conditions. Intervention is possible, but only within rhythms that cannot be forced.

In this way, the process itself becomes a quiet counter-narrative to extractive AI: one that values tending over acceleration, attunement over efficiency, and waiting as a form of work.