Disco for Darwin

2010-11

Photographic tests, conceptual installation project

Disco for Darwin (2010) is a conceptual project grounded in experimental photographic testing and extensive research into plant movement, early scientific visualization, and embodied time. The project takes as its starting point Charles Darwin and Sir Francis Darwin’s The Power of Movement in Plants (1880), a foundational yet often overlooked study that demonstrated how plants continuously move through slow, circular gestures known as circumnutation.

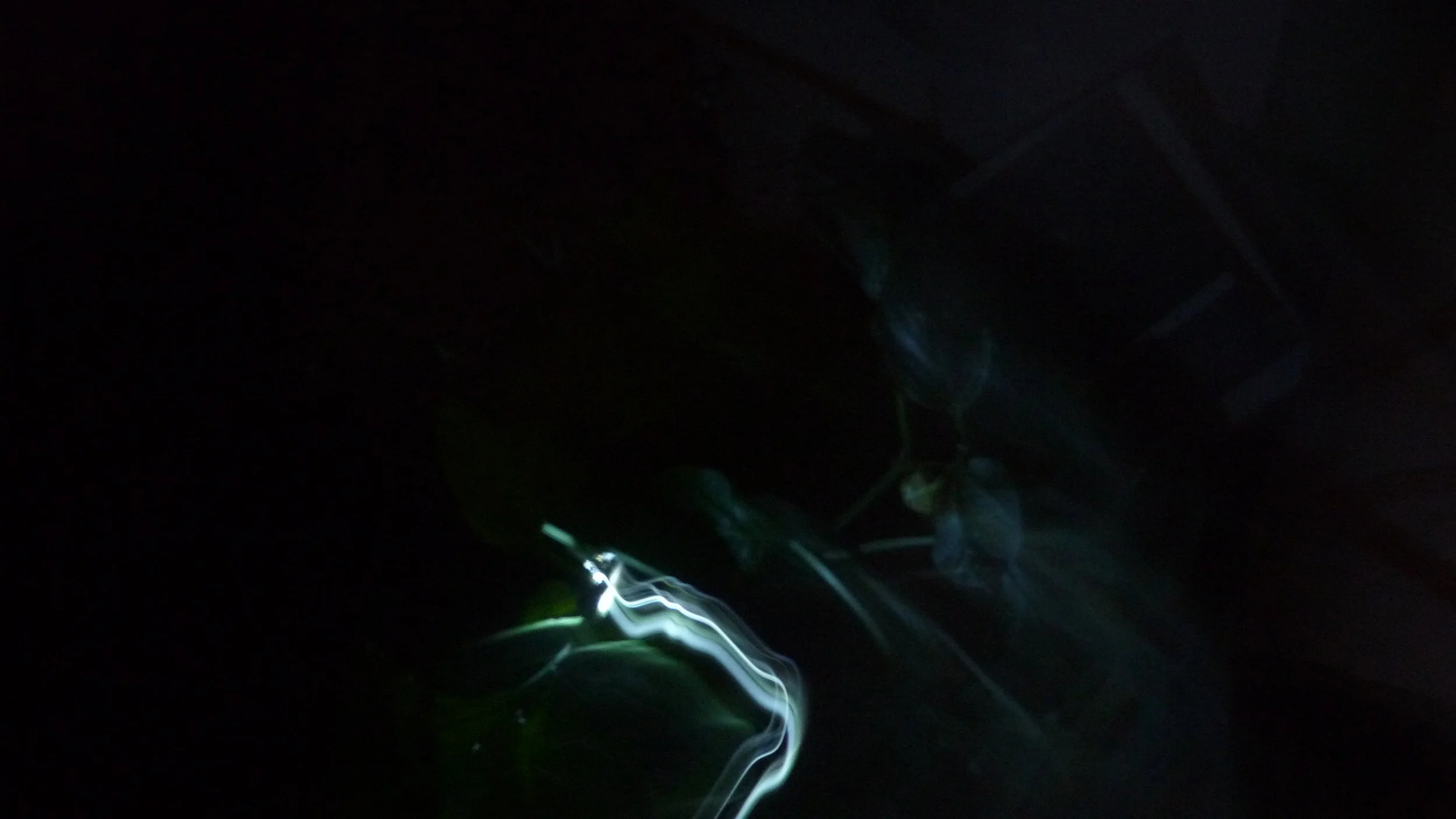

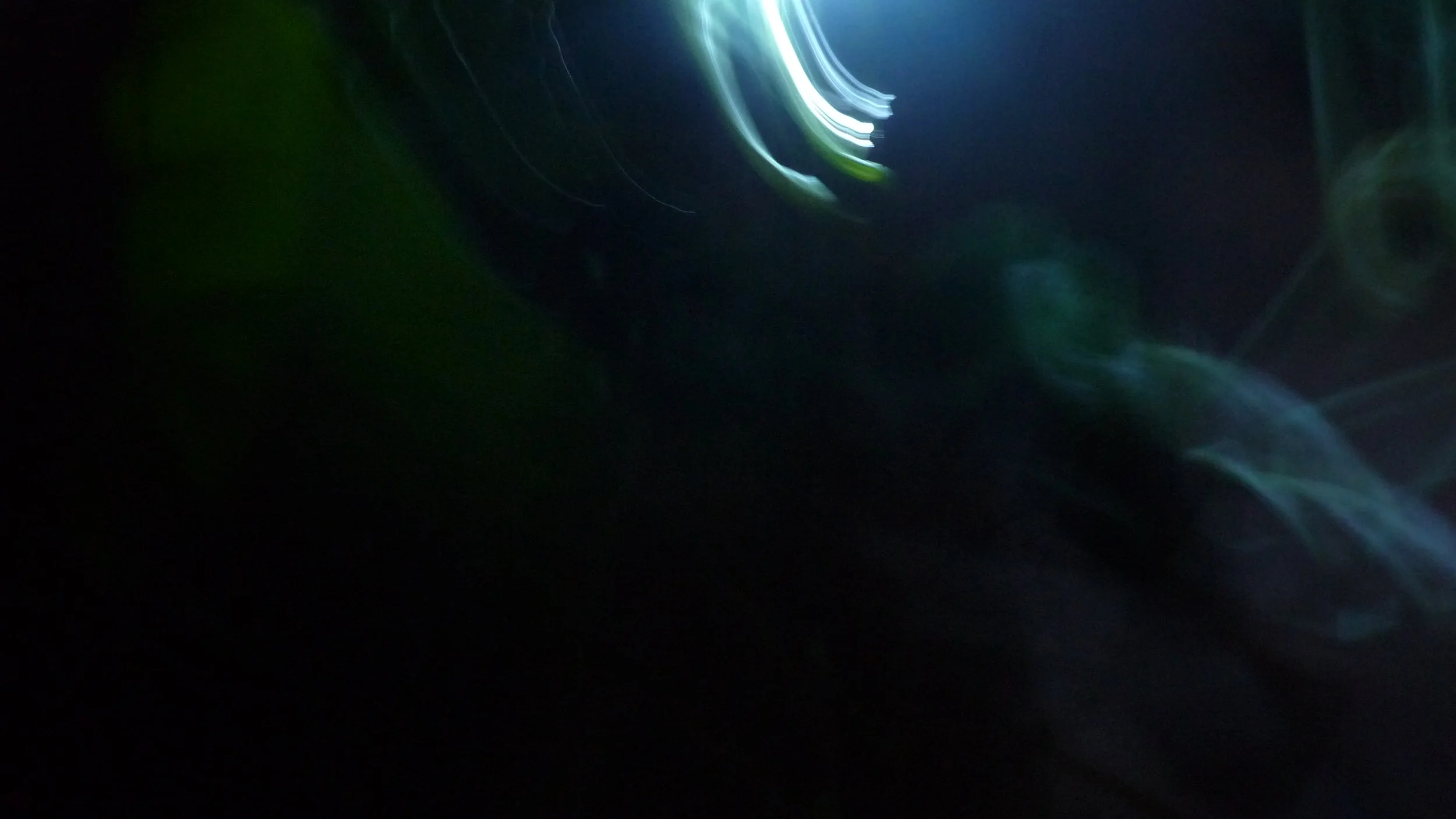

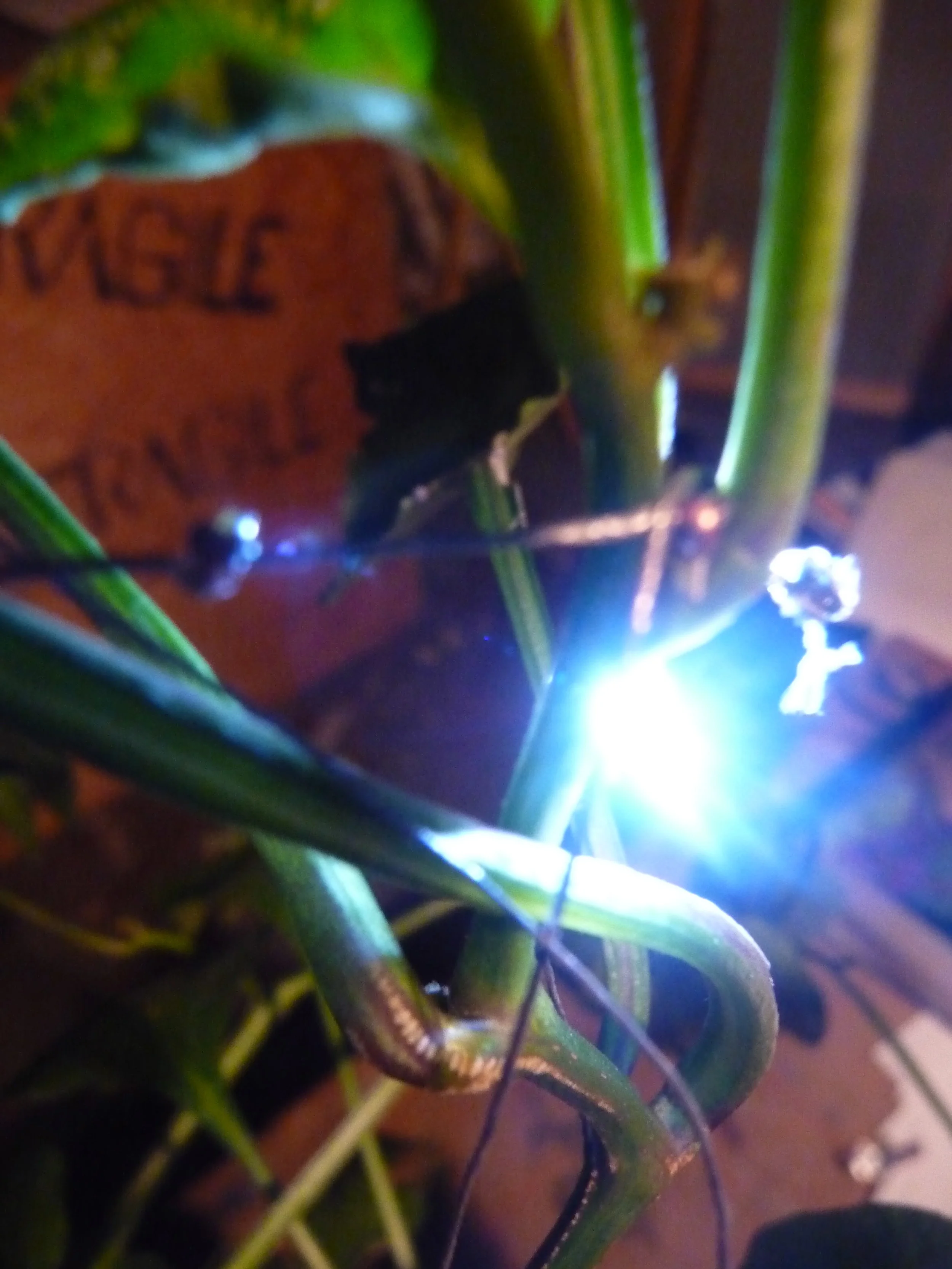

Darwin’s original experiments relied on analogue motion-tracking tools glass plates, ink, and small beads attached to growing plants to make imperceptible vegetal movement visible over long durations. These techniques attempted to bridge radically different temporal scales: plant time and human observation time. Disco for Darwin extends this lineage through contemporary materials and imaging technologies.

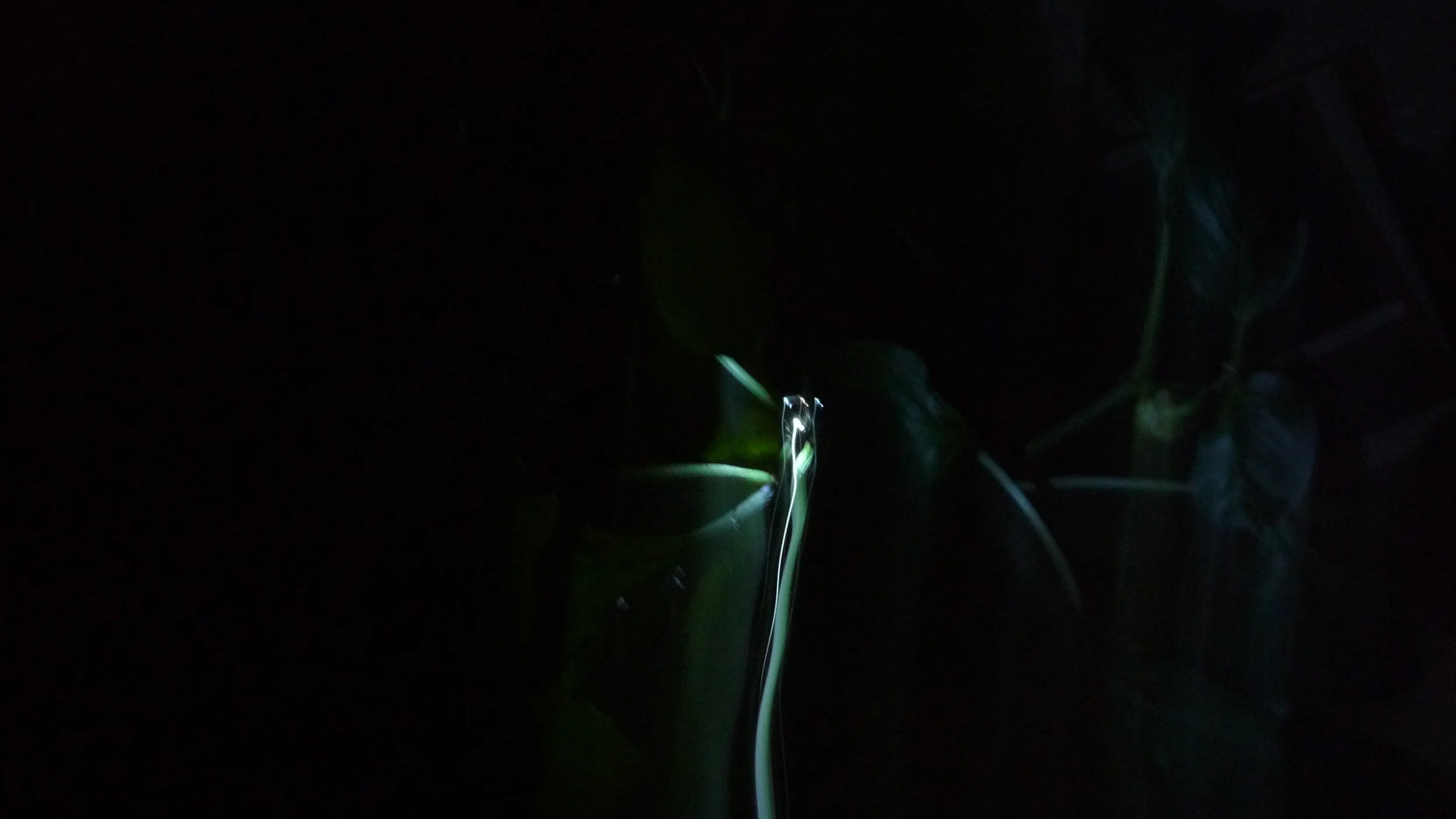

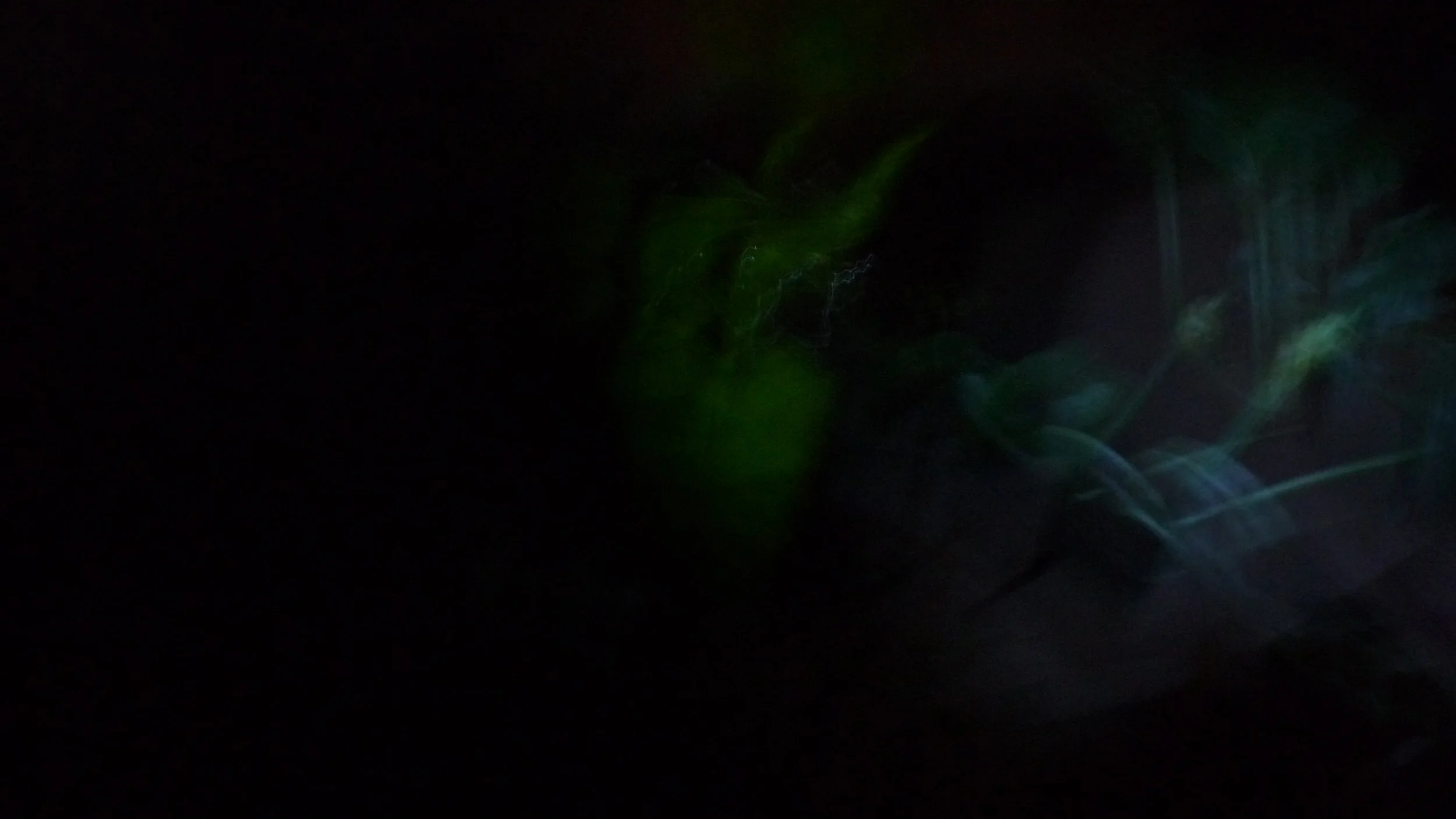

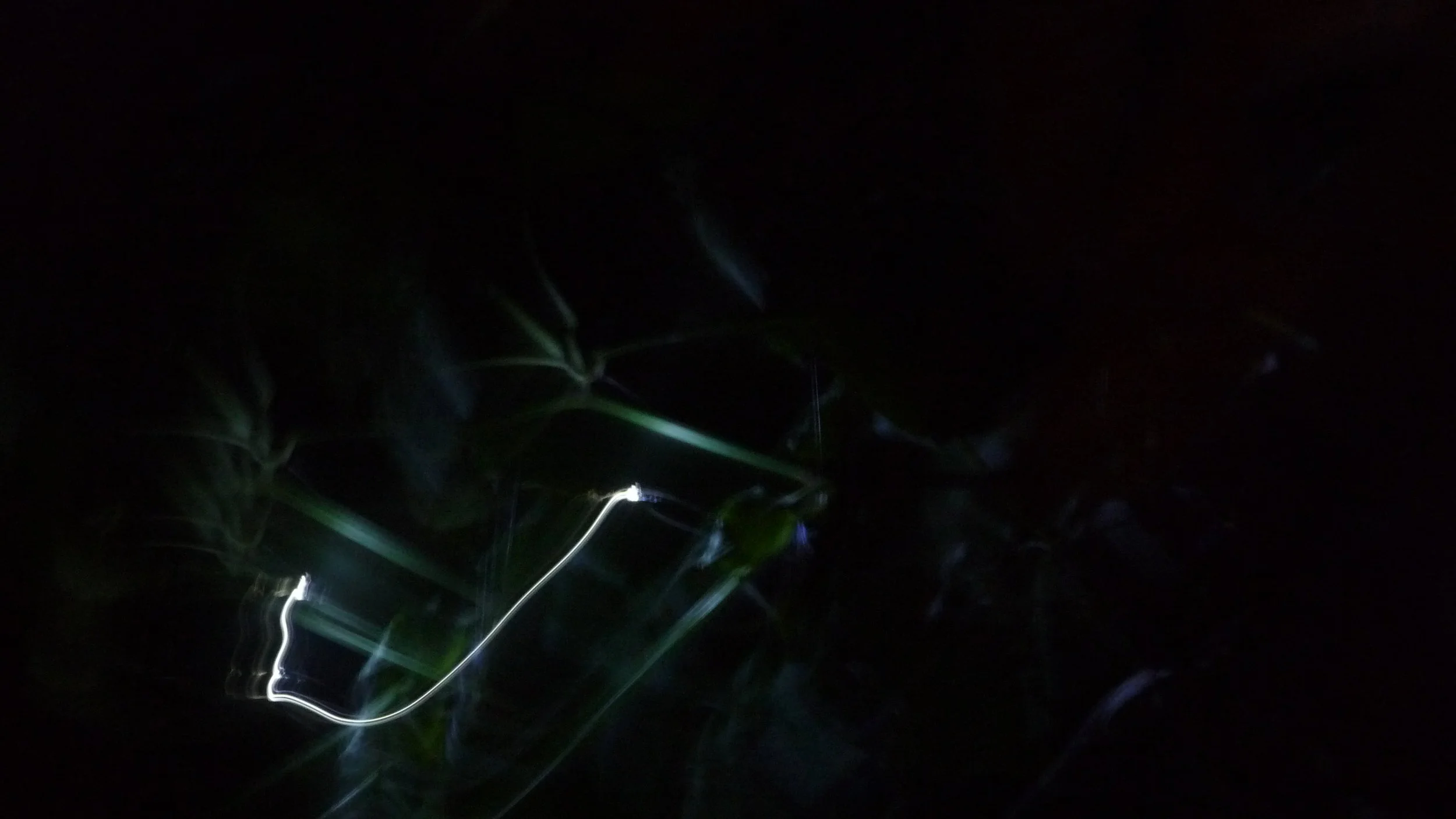

A series of photographic test works were produced using conductive thread, surface-mount LEDs, and slow-motion photography. The LED lights functioned as contemporary replacements for Darwin’s tracking beads, allowing plant movement to register as luminous traces rather than static marks. These tests explored how vegetal motion could be rendered legible through light, duration, and exposure, emphasizing that plant intelligence unfolds slowly, persistently, and beyond human urgency.

The broader project proposed an installation that would combine these photographic and video traces with ink-on-glass drawings, directly referencing Darwin’s original apparatus. These movement diagrams were intended to be translated into vinyl or stencil-based dance-step notations placed on the gallery floor, inviting human bodies to follow, echo, or rest within plant-derived choreographies. A site-responsive library of music for plants and people, would accompany each installation, reinforcing rhythm as a shared ecological language rather than a human imposition.

Although Disco for Darwin was widely proposed to exhibitions, residencies, and funding opportunities, the project remained unrealized at the scale originally envisioned. Nevertheless, the project’s photographic tests, conceptual framework, and research remain a vital part of an ongoing inquiry into plant movement, expanded choreography, and posthuman temporalities.

Disco for Darwin stands as an early articulation of themes that continue to shape my practice: attentiveness to more-than-human intelligence, the translation of ecological processes into sensory experience, and a refusal of productivity metrics that privilege speed over care. The work asks not how plants can perform for us, but how humans might learn to slow down enough to move with them.